‘You cannot write a history of bookbinding by just studying the decorated fine bindings as you cannot write a history on humanity by just studying the ascendancy.’

Dr Nicholas Pickwoad

The archaeology of the book

Over the three centuries no comprehensive history of bookbinding has been written.

The majority of bindings are common man bindings where binding practice is not documented. Apart from general binding manuals (1) we have no insight in the running of a bookbindery and how bookbinders went about in their daily practice. How and why books came to be with each its own distinct features can only deciphered from carefully studying these. These features are not the printed text but literally the non-printed characteristics making up the binding that holds the text. These characteristics give us clues on how a book came to be; they are the archaeology of the book. As books have become dilapidated as a result of handling and not always favourable conditions they have opened up at unintended places and reveal a hidden history.

Printed text however is of major importance in preserving and make accessible the book. From this point of view the ‘archaeological’ openings of the original binding are sacrificed for a restored and closed up re-binding and the library is happy to have a working copy again. In the process of repairing books conservators have ‘bulldozed through these archaeological sites’. If we broaden our view from the book as a medium of written information to that of an unique artefact with written information we will get an insight into the origins of the book.

The anatomy of the book

A few years ago a client gave me a shabby old book. It was The Anatomy of the Body of Man by Johann Vesling translated from Latin into English by Nicholas Culpeper, stitched cheaply in a sheepskin binding.

The cover was coming of and the text block was weakened by mould. The spine leather was coming away and the book opened up at an unintended point revealing four neat saw cuts as a likely preparation to sew the text block on recessed cords. The text block has however never been sewn but stitched on three alum tawed leather strips. The evidence of the unused saw cuts alerted me to be very cautious with conservation. It does not take a trained eye to see this prehistory, but in other books it might not be so apparent. It could be a dent in a paper edge or even a dust mark, which can indicate a prehistory of the book!

The reasons for the saw cuts are unknown: the book might have been set up to have been bound ‘properly’ on recessed cords but then the distribution of the cuts are a bit odd. Nicholas Pickwoad has seen many of them but each one was unique: “The saw cut on the far left is very close to the edge: it is where you would expect a kettle stitch instead of a cord.” (2)

Saw cuts were also used as a rapid binding method whereby they were filled up with glue to make a threadless binding. In this case the were no glue remnants to be found. The initial binding using the saw cuts has been overridden by stitching to speed up the binding process and to make it cost effective.

This is no wonder as bookbinders had to churn out 50 to 100 books a day and to reach that level bookbinders had to use economies like sewing multiple sections on one thread, bypass sewing stations. The Body of Man is done the cheapest and quickest way possible: stitched, no headbands, cheap sheepskin finish with just a few blind lines. De binding is just doing for what it was designed for: to spread the word.

After the invention of the printing press the ‘word came out’. Knowledge that was exclusively for scholars was made available to wider audiences by it.

What lies beneath...

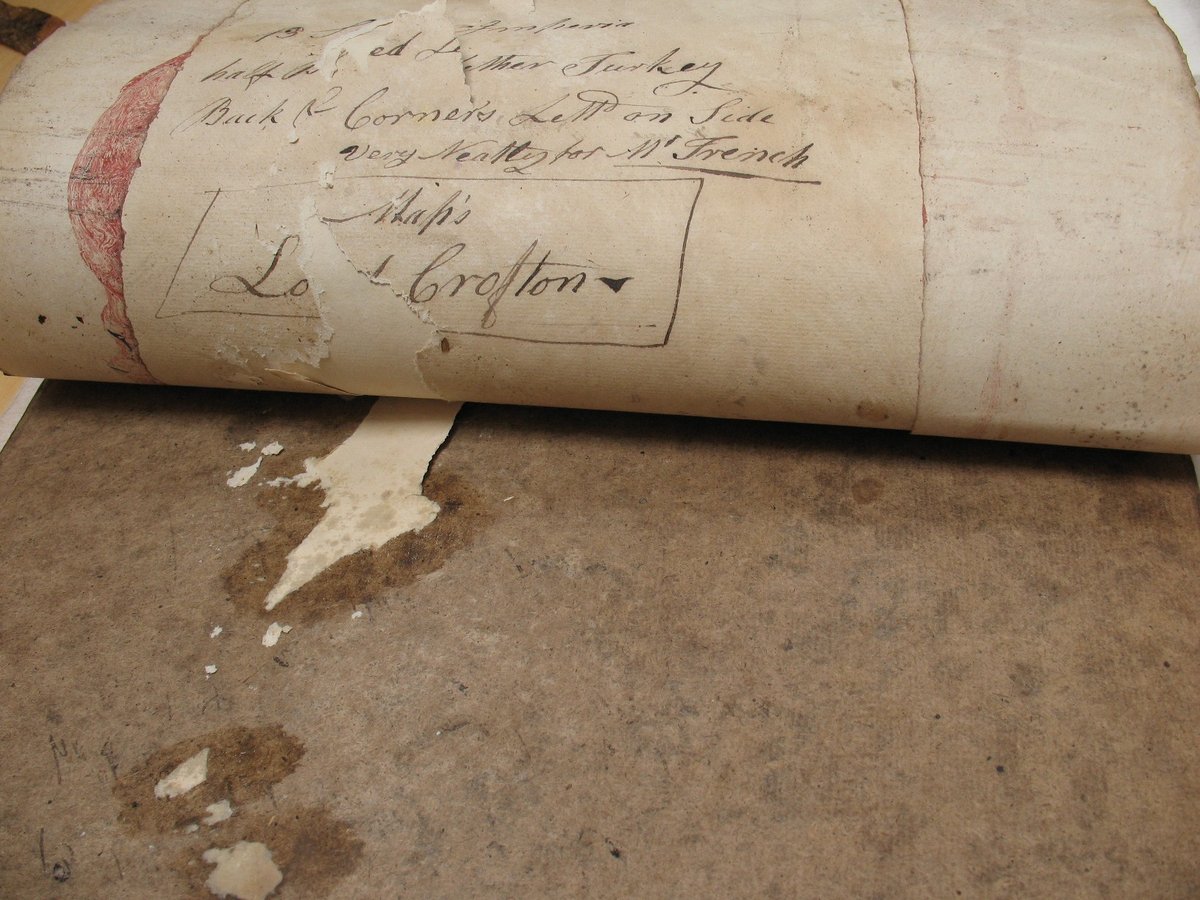

The opening up of a book can sometime reveal a written message, as is the case with Lord Crofton’s Map Book (1828) belonging to Roscommon County Archives. Here is an instruction to the binder of how the work should be executed. It reads:

13 Sheets Imperia - half B Red Lether Turkey – Back & Corners Lettd on Side – very Neatly for Mr French – Maps – Lord Crofton

The 13 sheets are bound as wished: in half goats leather imported from Turkey on back and corners with a title label on the front side.

Britain was restricted from buying goatskins from Morocco and had to find a trade loophole in Turkey in order to obtain skins. Hence the name Turkey leather for a British or Irish binding, Marocin or Marokijn if it would be a French or Dutch binding. Very neatly means that the edges were cut making it a fine presentation binding for Mr French.

Opening up the paste down not only revealed a binders’ notice but also the use of dark brown rope fibreboard. Rope fibreboard is made of rigging and only in the British Isles. It is just one of the of the regional variations one may encounter when peeking into archaeological openings of books, let alone all the other variations of binding practices, hand skills, materials use, work economies etc. that make bindings between the invention of the printing press and the steam engine so ‘colourful’. Old books tell a history beyond their printed content in how they have come to existence. It is up to the beholder to ‘read’ these.

More binders traces

Not all archaeological evidences present themselves so clear-cut.

In this Handbill of The Jackie Clarke Library and Archives the evidence that this paper has at some stage been bound was easily overlooked. Yet it shows again saw cuts and even I small bit of animal glue proving its previous bound state, this to the excitement of the curator wondering if there still might be a copy of the bound volume in existence somewhere. That it has been bound is all we know. But here ends the facts and we only assume the rest. We don’t know what the rest of the book might comprise, maybe it was a bundle of same bills, to be torn and handed out to the sleeping people of Ireland.

Removing the one-millimeter glue bit is removing evidence of its former bound state and clues that might lead to answers.

Notes

-

The first description of the trade of bookbinding was written by Anselm Faust, Der Buchbinder, 1568

-

In the post script of the third edition of Bernard Middletons, Restoration of Leather Bindings by Nicholas Pickwoad there is an identical case to that of the Anatomy of the Body of Man: A copy of George Bishop, A looking-glass for the times being a tract concerning the original and rise of truth and the original and rise of the antichrist, London, 1668 shows the same unused saw cuts and stab stitching. The Houghton Library has decided to leave the book in this condition for that reason.

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.